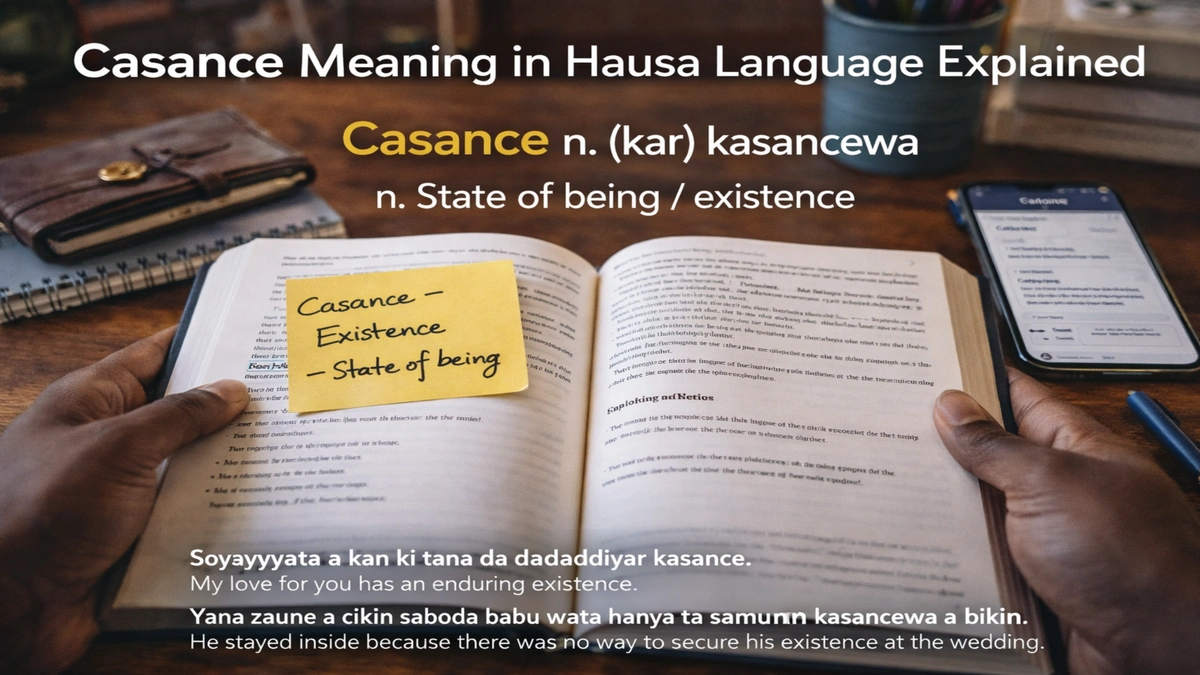

i came across the word “casance” not in a textbook but in a quiet question about meaning. What does it really say when Hausa speakers use this word so frequently and with such confidence? In the first moments of explanation, the answer sounds simple. Casance, more accurately spelled kasance, is a Hausa verb meaning “to be,” “to exist,” or “used to.” Yet that simplicity fades as soon as the word is placed into real speech.

In Hausa, a major language of northern Nigeria and Niger, kasance does not simply label existence. It carries the weight of habit, continuity, and expectation. It allows speakers to describe what was once true in a lasting way and what tends to be true over time. When someone says Bello ya kasance yana kai kaya Lagos, the sentence does more than state a past job. It suggests routine and identity. Bello was known for this work. It defined him for a period.

Many people encounter “casance” online and struggle to place it. Some assume it is a brand name. Others confuse it with Casamance, a region in Senegal. Linguistically, the strongest match is Hausa. The spelling variation usually reflects phonetic hearing or second-language writing rather than a separate word.

Understanding kasance means understanding how Hausa handles being itself. This article explores its meaning, grammar, pronunciation, cultural role, and related verbs. By the end, the word becomes more than a translation. It becomes a way to see how language shapes experience.

From Casance to Kasance: Understanding the Spelling

The spelling “casance” appears frequently in informal writing, especially outside West Africa. Hausa uses a Latin-based writing system known as Boko, in which the letter c represents a “ch” sound, not a hard “k” or “s” as in English. The correct standardized spelling is kasance.

Spelling confusion often arises when learners hear the word before seeing it written. The soft consonant and flowing syllables can easily be rendered as “casance” by ear. This does not indicate a different meaning. It reflects how sounds travel across languages and keyboards.

Hausa orthography was standardized in the twentieth century, and kasance appears consistently in dictionaries and teaching materials. Recognizing the spelling matters because it determines whether learners can find accurate definitions and examples. Once the spelling is clear, attention can shift to how the verb actually works.

Core Meaning of Kasance in Hausa

At its core, kasance is a verb of state. It expresses being rather than action. However, Hausa does not treat being as static. Instead, it places states within time, habit, and social expectation.

Kasance can mean “to be,” “to exist,” or “used to,” depending on context. Unlike English, which separates these ideas into different constructions, Hausa allows one verb to stretch across them. The meaning is shaped by accompanying words that indicate tense and aspect.

For example, ya kasance often points to something that was characteristically true in the past. Zai kasance suggests a future tendency or expected condition. The verb rarely stands alone. It works with markers that situate the state within time.

This flexibility allows speakers to describe life as ongoing rather than fixed. A role, a habit, or a quality can be presented as something that defined a period without locking it permanently in the past.

Grammar and Sentence Structure

In Hausa grammar, kasance usually appears in complex verb phrases. It often combines with participial forms such as yana, suna, or tana, which describe ongoing action or state.

Consider this sentence: Mata sun kasance suna yin aiki a gona. Literally translated, it means women were in the state of working on the farm. In natural English, it becomes women used to work on the farm. The Hausa structure highlights continuity rather than a simple completed past.

Another example is Ya kasance mai kyau a daren yamma. This can mean he tends to be good in the evening. The sentence does not lock the behavior into a single moment. It frames it as a recurring pattern.

Understanding this structure helps explain why learners sometimes misuse kasance. In contexts where Hausa prefers descriptive constructions without a verb of being, kasance can sound heavy or unnatural. Knowing when to omit it is part of fluency.

Everyday Usage in Spoken Hausa

In daily speech, kasance is common in storytelling, reflection, and explanation. Elders use it to describe earlier ways of life. Parents use it to explain children’s habits. Speakers use it to clarify expectations.

Common examples include statements about work, character, and routine. The verb signals that what is being described was not accidental. It was normal. It happened often enough to matter.

This quality makes kasance especially useful in oral cultures, where memory and habit define identity. The word helps speakers organize the past without reducing it to isolated events.

Pronunciation and Tone

Hausa is a tonal language, meaning pitch affects meaning. Kasance is typically pronounced with a light rise at the beginning and a falling tone at the end. A common phonetic rendering is ká-sàn-cé.

The first syllable is lightly stressed. The middle syllable is short. The final syllable ends with a soft “ch” sound. Misplacing tone can make speech sound foreign or unclear, even if the consonants are correct.

Listening is essential for learning this word. Hearing it in full sentences helps learners internalize both tone and rhythm. Written descriptions alone rarely capture the sound accurately.

Kasancewa and the Language of Existence

From kasance comes kasancewa, a noun meaning existence or state of being. This form appears in more abstract contexts, including philosophy, religion, and formal writing.

Kasancewa allows speakers to discuss being as a concept rather than a situation. It is used when talking about identity, reality, or moral states. This transformation shows how Hausa builds abstract meaning from everyday verbs.

The relationship between kasance and kasancewa mirrors how lived experience and reflection connect. One describes what is or was. The other names the condition itself.

Related Verbs and Semantic Neighbors

Hausa does not rely on a single verb to express being. Instead, it uses a network of related verbs that overlap in meaning.

Zauna means to stay or remain, often implying physical presence or settlement. Yi is a general verb meaning to do, but it can describe states in certain constructions. These verbs share space with kasance but serve different functions.

Understanding their differences helps avoid oversimplification. Where kasance highlights habit and continuity, zauna emphasizes remaining in place. Where yi describes qualities, kasance frames patterns over time.

Cultural and Religious Dimensions

In religious Hausa speech, especially Islamic teaching, kasance often carries ethical and future-oriented meaning. Statements about justice, unity, or divine order frequently use the verb to describe conditions that must be fulfilled.

For example, a sentence stating that true divine rule will not exist until certain conditions are met uses kasance to project moral expectation into the future. The verb becomes a bridge between belief and behavior.

This usage reflects how language and values intertwine. A verb of being becomes a tool for teaching responsibility and hope.

Common Misunderstandings

Learners often assume kasance functions exactly like the English “to be.” This leads to overuse. In many present-tense statements, Hausa uses descriptive structures without any verb of being.

For instance, ni dalibi ne means I am a student. Adding kasance would change the meaning, suggesting a past or habitual role instead of a current fact.

Recognizing these distinctions is essential for accuracy. Hausa grammar rewards sensitivity to context rather than direct translation.

Takeaways

• Casance is a variant spelling of the Hausa verb kasance.

• Kasance expresses being, existence, and habitual past.

• The verb emphasizes continuity rather than isolated events.

• Pronunciation and tone are essential to correct usage.

• Kasancewa extends the verb into abstract ideas of existence.

• Understanding when not to use kasance is part of fluency.

Conclusion

i see kasance as a quiet but powerful word. It does not rush to define. It allows space for habit, memory, and change. In Hausa, being is not frozen in time. It is shaped by what people tend to do and how long they do it.

Learning this word offers more than vocabulary. It offers insight into how language can frame life as a series of lived patterns rather than fixed states. In a world that often seeks sharp definitions, kasance reminds us that existence is often something we grow into, live through, and remember.

Understanding kasance is not only about Hausa. It is about recognizing how languages everywhere find ways to hold experience gently.

FAQs

What does casance mean in Hausa?

Casance is a variant spelling of kasance, meaning to be, to exist, or used to, depending on context.

Is casance the correct spelling?

The standardized Hausa spelling is kasance. Casance reflects phonetic variation.

How is kasance used in sentences?

It often describes habitual past actions or tendencies rather than single events.

What is kasancewa?

It is the noun form meaning existence or state of being.

Is kasance still used today?

Yes. It remains common in modern spoken and written Hausa.