In the complex and often unregulated world of adult entertainment, certain productions stand out not only for their content but for the intense public discourse they ignite. GhettoGaggers is one such production — a name that for many conjures immediate discomfort, controversy, and a clash of ideologies. Known for its extreme scenes, racial overtones, and unapologetically aggressive dynamics, GhettoGaggers has occupied a contentious space at the intersection of pornography, race, and media ethics for nearly two decades.

This article seeks to unpack the cultural context of GhettoGaggers, tracing its origins, controversies, and its broader implications on how society views race, gender, power, and consent in adult content.

A Brief History: The Emergence of Extreme Adult Content

GhettoGaggers emerged during the mid-2000s, a period of rapid transformation in the adult entertainment industry. With the internet democratizing access and production, niche content proliferated. What had once been a studio-dominated, VHS-distributed industry became an open frontier for low-budget, high-shock-value operations. In that environment, GhettoGaggers took root.

The website, part of a network of similar shock-style adult sites, quickly gained notoriety. Its scenes featured mostly Black women — often newcomers — in interracial scenes that were aggressive, humiliating, and racially charged. The site drew immediate criticism, with detractors calling it exploitative and deeply racist. Supporters, on the other hand, framed it as extreme fantasy content — legal, consensual, and reflective of demand in niche corners of the market.

Race and Power in Pornography

The adult industry has long commodified race and fetishized stereotypes. From “ebony” and “Latina” categories to so-called “interracial” scenes that almost always pair white men with non-white women, the framing of race in porn is hardly neutral.

But GhettoGaggers stands out for how overtly it capitalizes on those dynamics — and intensifies them. It weaponizes language, degradation, and props in ways that mimic historical patterns of racial subjugation. Critics argue that this isn’t just fantasy; it’s a reenactment of trauma, wrapped in the illusion of consensual kink.

Academics and activists have voiced concern that the line between performance and real-world prejudice blurs in such productions. “What does it say about our society when such violent portrayals of Black women become profitable entertainment?” asks Dr. Alisha Morgan, a media studies professor at Howard University. “It reflects not only the tastes of a few, but the permissiveness of a cultural framework that still views Black female bodies as inherently deviant.”

Consent, Coercion, and the Legal Gray Areas

Proponents of GhettoGaggers argue that all scenes are consensual. Legally, the performers sign contracts, provide ID, and — by the standards of the industry — give informed consent.

But critics question the power dynamics at play. Many of the women featured are economically disadvantaged, inexperienced, and unaware of the site’s notoriety before shooting. Interviews with former performers paint a picture of misleading expectations, emotional distress, and long-term reputational damage.

“There’s a huge difference between legal consent and ethical production,” says Erika Jones, a former adult actress turned advocate. “When a woman is told it’s just a rough scene and ends up being spat on, choked, and degraded racially while cameras roll — we have to ask whether she really knew what she was signing up for.”

The industry’s lack of centralized oversight makes it difficult to regulate productions like GhettoGaggers. Unlike mainstream studios, niche and extreme content sites often operate with minimal transparency, further muddying the waters around ethics.

Public Response and Activist Backlash

In the late 2010s, a wave of social justice movements — including #MeToo and Black Lives Matter — brought renewed scrutiny to institutions that perpetuate racial and gender-based violence. GhettoGaggers, along with other extreme adult sites, came under fire for its imagery and message.

Online petitions, op-eds, and academic critiques flooded the discourse. Some argued that the site should be taken down entirely. Others saw it as an expression of free speech, and of the right to explore taboo fantasies in a consensual framework.

Still, the growing visibility of these critiques forced platforms to reconsider. Payment processors like Visa and Mastercard, under pressure, began cutting ties with high-risk adult sites. Though GhettoGaggers remained online, its influence waned amid the broader crackdown on unregulated pornographic content.

The Performer Perspective: A Spectrum of Voices

It’s essential not to generalize the experiences of performers. Some who have appeared on GhettoGaggers have defended their involvement, citing high payouts and asserting that they maintained agency throughout the process.

“I knew what I was doing,” says one anonymous performer interviewed in 2022. “I didn’t feel disrespected. It was a role, like any other scene. I got paid. I moved on.”

Others, however, expressed regret and described the experience as traumatic.

“I walked in thinking it was a standard hardcore scene,” said another performer. “I ended up being called names, spat on, and made to cry on camera. It haunts me.”

This spectrum of experience highlights the complexity of consent, especially when economic desperation, racial fetishization, and industry inexperience are involved.

The Fetish Economy and the Algorithmic Age

One cannot analyze GhettoGaggers without addressing the algorithmic engine behind adult content. The rise of tube sites and data-driven porn recommendations means that what people watch informs what gets produced.

If users click on degrading scenes — especially those with Black women — the algorithm recommends similar content, driving traffic and, ultimately, profits.

Pornhub, Xvideos, and other adult platforms have been complicit in amplifying racially charged content. Tags like “ghetto,” “ratchet,” and “black slut” remain common, despite growing calls for reform.

This digital economy of fetishization has real-world implications. It shapes desires, normalizes certain portrayals, and blurs the line between fantasy and systemic bias.

The Cultural Mirror: What GhettoGaggers Reveals About Us

In many ways, GhettoGaggers is less about porn than it is about society.

It reflects long-standing American tensions around race, power, and sexuality. It forces uncomfortable questions: Why does content that degrades Black women appeal to a sizable audience? What cultural baggage is being unpacked — or repackaged — in such scenes? And what responsibility do creators, consumers, and platforms bear in regulating this content?

At its core, GhettoGaggers challenges the notion that pornography is merely private entertainment. In a world where adult content is more accessible than ever, it becomes a cultural artifact — revealing what we desire, what we tolerate, and what we deny.

Toward Accountability and Change

Calls for ethical reform in the adult industry are growing. Performers are demanding more transparency, platforms are being held to higher standards, and consumers are being asked to reflect on their viewing habits.

Some creators have responded by developing “ethical porn” — content made with performer input, fair pay, and a focus on mutual respect. Others are pushing for centralized unions and third-party oversight, similar to protections found in mainstream film industries.

Whether sites like GhettoGaggers can — or should — evolve in this new landscape remains an open question.

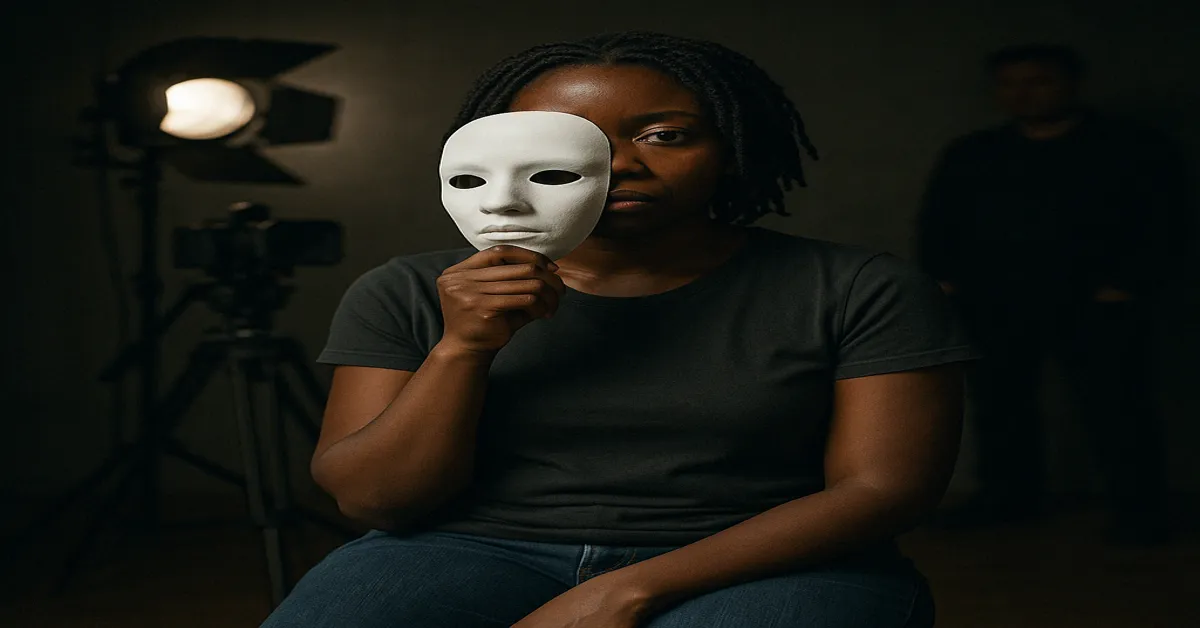

Conclusion: Porn as a Mirror, Not a Mask

GhettoGaggers may exist on the fringes of adult entertainment, but its influence reaches far into conversations about race, gender, consent, and digital ethics.

To dismiss it as “just porn” is to ignore the deeper forces it reveals — the power imbalances it dramatizes, the historical wounds it reopens, and the societal silence it often exploits.

As adult media becomes more ubiquitous and more visible, the responsibility to question, to critique, and to demand better from both producers and ourselves becomes not just ethical — but necessary.